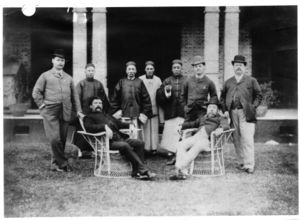

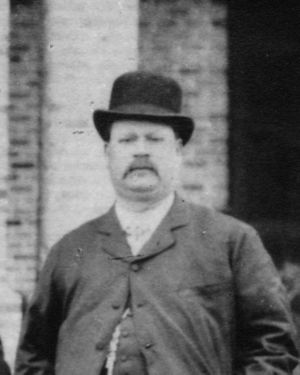

Henry Bridges Endicott

| Henry Bridges Endicott | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Shanghai |

| Died |

5 January 1895 Shanghai |

| Resting place | Shanghai |

| Nationality | American |

Contents

Biography

Service

Henry B. Endicott joined Butterfield & Swire

as Head Shipping Clerk in February 1873,

after being headhunted from the US firm

of Augustine Heard & Co. An American and

a fluent Chinese speaker, he was known to

have excellent connections throughout the

chartering and shipping community, and John

Samuel Swire believed he was the right man

for what he envisaged would be a fight to the

death with China Navigation’s main rival on the

Yangtze, the Shanghai Steam Navigation Co.

Endicott more than justified his faith,

building CNCo into the most profitable

company on the river and seeing Shanghai

SNCo - controlled by the American firm,

Russell & Co. - collapse into bankruptcy.

On the coast, it was his skilful management

and tactful negotiations with shippers that

saw CNCo secure a monopoly of the lucrative

‘beancake’ trade. During his 21 years with

B&S, Endicott was one of its highest paid

employees, on a par with Swire’s Shanghai

Taipan. His position was unique and he made

himself indispensable - a fact that tended

to frighten Shanghai management, who felt

they had created a monster: ‘We raised up

E. into a one-man department’ admitted one

Taipan, Edwin Mackintosh, ‘Lang [his own

predecessor] was too ignorant and supine to

control him.’

Endicott’s right-hand was CNCo’s

first comprador, Cheng Kuan-Ying. Born in

Guangdong province in 1842, Cheng had been

comprador to the Union Steam Navigation

Company - the bankrupt Yangtze company

bought out by CNCo in 1872, as the basis for

its incipient operations. The role of comprador

involved canvassing, or ‘drumming’ for cargo

and passengers, passenger ticketing and

management of the company’s godowns.

It was a senior position of implicit trust and

as Cheng would later write: ‘All matters

relating to the promotion of freighting business

and to personnel were handled by myself,

in consultation with the American, Yen-er-chi

[Endicott].’

The pair made a ruthless team and

some of their imaginative, if questionable,

canvassing methods would have startled

their Taipan, had he known of them at the time.

When Russell’s were suspected of offering

sweeteners to charterers to secure cargo,

Endicott had no qualms about doing the same.

Russell’s Manager, R.B. Forbes, was soon

bleating: ‘Cargo promised to us is taken away

to their steamers, ...our oldest and best friends

among local freight agents tell us that the

opposition offers so much better terms...’.

In 1882, Cheng moved on to greater

things when he accepted the position

of Assistant Manager of the government controlled

China Merchants Steam

Navigation Co. - a company that had come

into being at about the same time as CNCo

and had rapidly grown in importance, taking

over the Shanghai SNCo after its bankruptcy

in 1877. He later wrote that it was with mixed

feelings that he eventually took the decision

to leave Swire, because of his high regard

for the firm’s business ethics. On Cheng’s

recommendation, his protégé, Yang Kwei

Hsian, took over his role of CNCo comprador

alongside Endicott. But, two years later,

Yang suddenly committed suicide and it was

discovered that he had been pocketing large

amounts of CNCo freight. For fraud on such a

scale to have gone undetected pointed to an

inexplicable lack of judgement on Endicott’s

part: naively, he had assumed he could

place the same level of trust in Cheng’s

chosen successor.

In customary fashion, comprador Yang’s

good character had been secured by three

financial guarantors – one of whom was

Cheng. But the amount of the loss was so great

that the men had no hope of repaying it. The

matter ended in court and was finally settled

with CNCo writing off half the amount, while

Yang’s guarantors gave promissory notes for

the balance - which they duly honoured. It was

a costly lesson and highlighted the iniquities

of the outmoded comprador system.

Endicott was left to lick his wounds – and to implement far stricter controls on the collection of freight monies. He never quite recovered his indomitable position – though his part in the success of CNCo’s early decades is undeniable. He died from a heart attack in 1895, at the age of 73, resisting all attempts to persuade him to retire and hand over the reins of CNCo to a younger man.