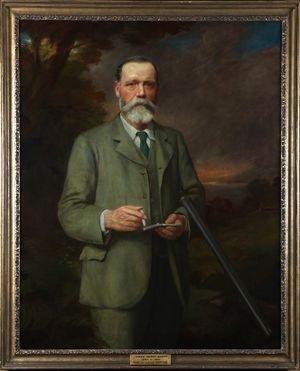

James Henry Scott

| James Henry Scott | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 20 July 1845 |

| Died |

October 22, 1912 (aged 67) Edinburgh |

| Spouse(s) | Emily Reid Yuill |

| Parents | Charles Cunningham Scott and Helen Rankin |

Contents

Biography

James Henry Scott, Senior Partner of John Swire & Sons

Limited from 1898 until his death in 1912, had a major role

in developing Swire’s early industrial interests, which would

later be redeveloped as an extensive property portfolio.

Jim Scott was the third son of C.C. Scott, Chairman of Scott’s

Shipbuilding & Engineering. He left Liverpool for Shanghai in

the Blue Funnel steamer Achilles on 27th September 1866,

at the age of 21. In his pocket was a letter from Alfred Holt to

John Samuel Swire, asking him to give the young man a trial

as a shipping clerk. So began Scott’s life-long connection

with the firm of Butterfield & Swire.

John Swire had recently arrived in Shanghai and was

in the process of establishing his new House; it consisted

of Swire, himself, as taipan, two specialists to handle

Manchester (cotton) and Yorkshire (woollen) goods, young

Jim Scott as bookkeeper and general clerk, and an office

‘junior’. As Scott later recalled: ‘In those days firms in

China found the members of their staff in board and lodging.

Butterfield & Swire being then small, all dwelt in the same

house and messed together, the clerks having the privilege

of asking their friends to dine when the taipan was out,

but at no other time’. As newly appointed agents for Blue

Funnel, there was much to learn: ‘as no one in the newly

started firm knew anything of custom-house work, it was

a case of groping in the dark for the young shipping clerk’.

Despite this unpromising beginning, Scott clearly had

aptitude and, by the age of 24, Swire had arranged for him

to take charge, on a temporary basis, successively of the

Yokohama and Shanghai offices; he took over the new Hong

Kong head office from the end of 1870. Between bouts of

ill-health, which forced him home to the UK for extended

periods, Scott would spend the remainder of his career in

the East alternating between Hong Kong and Shanghai. He

was made a partner of John Swire & Sons from 1st January

1874 and on John Swire’s death in 1898, took over as its

Senior Partner — the news reaching him by telegram as he

stepped off a P&O steamer at Singapore.

In spite of a 20-year age difference, Swire and Scott

were firm friends through thick and thin and Swire trusted

his judgement implicitly. Scott spent a year and a half

helping to run the UK end of the business while John Swire

travelled east in 1873, and was installed in Swire’s London

flat with instructions to ‘treat it as your own’. On John

Swire’s return in 1874, it was Scott who suggested he take

a look at two brand new coastal steamers up for sale cheap

at the family shipyard and so precipitated the expansion

of China Navigation’s interests from the Yangtze onto the

China Coast. And it was Scott who was sent to scout the

location for the proposed Taikoo Sugar Refinery in Hong

Kong in 1881 — diligently inspecting the site (by boat) during

a typhoon, in order to gauge how sheltered it would be.

Less happily, it was Scott who in 1884 had to break the news

to John Swire, once again visiting China, that his Shanghai

comprador had committed suicide having been uncovered

in major embezzlement of the China Navigation Company.

Of his role as Senior Partner from 1898, following

John Swire’s death, Scott said that he did his ‘best to

maintain the high reputation of the firm, and to carry on the

business on the lines [Swire] followed’. However, he also

proved to be a decisive and far-sighted leader: keen to

steer the firm into new areas of interest; pragmatic in

retrenching businesses that failed. He invested in a cold

store in the Philippines, established a tug and lighter

business to carry transhipped cargo up the Hai River

to Tianjin, and made the hard decision to cut China

Navigation’s prestige Australia line when cabotage and

immigration restrictions rendered it unviable.

James Henry Scott is principally remembered for

two initiatives which would have a lasting impact on

Hong Kong, his adopted home of so many years. The first

was Taikoo Dockyard, the construction of which he put

in train from 1900 — John Swire having fiercely resisted

‘the dockyard scheme’ and declared the sugar refinery to

be his ‘last child’. Scott identified and purchased a plot of

land to the east of the refinery compound and the family

firm, Scott’s Shipbuilding, acted as expert advisors. It was

a brave move, given the scale of the undertaking and the

huge capital investment. The dockyard took eight years to

construct, its opening coinciding with a world-wide slump

in shipping that was to last several years. Jim Scott lived

long enough — just — to see Taikoo build its first ships,

but not to see it return a profit.

Scott is also remembered as the leading voice

amongst Hong Kong’s British business community who

spoke out in support of the foundation of the University

of Hong Kong. The majority of the hongs insisted that an

enlarged, western-educated, Chinese middle class would

usurp British commercial supremacy, but Scott spoke of

his ‘deep-rooted belief in the great advantages that are likely

to accrue to the Colony’. And he put his money where his

mouth was, endowing the university with a substantial sum

and creating a chair of engineering. With typical modesty,

he demurred when it was suggested it be named the Scott

Chair, and so instead the Taikoo Chair of Engineering came

into being.

Scott married Emily Yuill, sister of a B&S colleague, George Yuill (who later became Swire’s agent in Australia) and, after her death, Mina Dunlop. Two of his sons and two grandsons became directors of John Swire & Sons; one of the latter, Edward Scott, went on to become Chairman of the Swire group. James Henry Scott died on 22nd October 1912; like his predecessor, he never retired: managing the firm he had seen come into being was not just his job — it was his life.